How Extism Built SDKs for Dozens of Languages in Months, Not Years

06 Nov 2025When we started the Extism ecosystem in 2022, the main challenge we had was the scale of SDK languages we needed to support. The goal for 1.0 was to run Wasm plug-ins from inside any application written in any language.

Since the core of Extism is a rust library, that means writing and maintaining a bindings SDK for every language out there. Without some kind of unified approach, each SDK requires a lot of overhead. It takes particular knowledge of writing an extension for the language, managing memory and ownership concerns, and maintaining it as the core library is evolving and churning in the early days. But, with our approach and a team of three, we were able to do this in a matter of months.

I’ve seen this type of deployment pattern come up a lot, with a single native core and a language ecosystem around it, so I thought I’d write a little about how we tackled the problem and how I might do it differently if we started over today.

Extism started with a C ABI

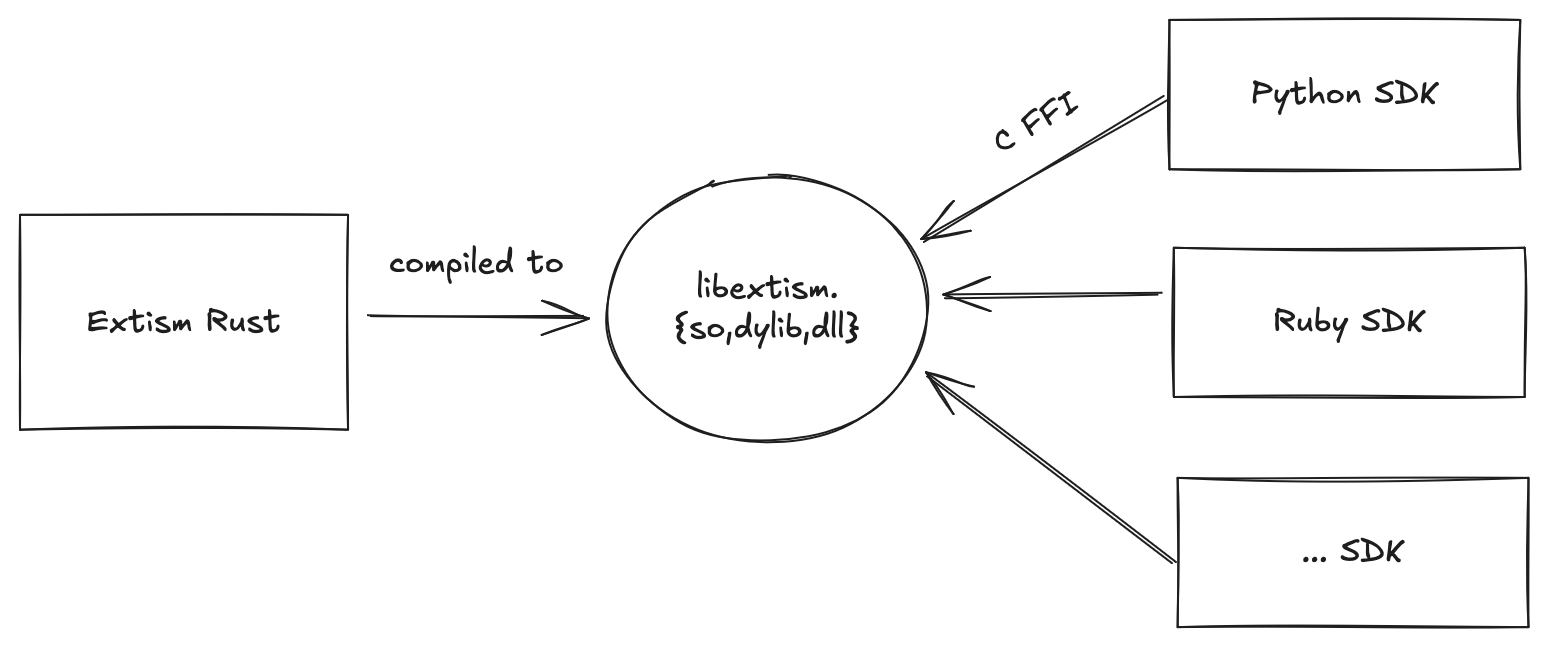

The core idea was, instead of writing custom extensions for each language,

we distributed the library as a single, native shared object we called libextism.

Each SDK is a light wrapper that loads this library via dlopen

or equivalent and speaks to it via FFI.

Shipping the library with a C ABI interface is the lowest common denominator of all languages. Every language can call into C functions and most have very mature tools to manage this.

Step 1: Write the C ABI

If you’re writing C or C++, creating this shared object is pretty simple. If you’re using rust,

you’ll need to create a module that exports all your c types and maps to and from rust using extern "C"

For example:

// Types must have a c representation

#[repr(C)]

pub struct ExtismVal {

t: ValType,

v: ValUnion,

}

// Functions can be exported using `extern "C"`

#[no_mangle]

pub unsafe extern "C" fn extism_current_plugin_memory_length(

plugin: *mut CurrentPlugin,

n: ExtismMemoryHandle,

) -> Size {

// ...

}

Step 2: Distribute

Set up a GitHub action to compile to all the targets you want to support and create release artifacts. You want to compile with the crate type cdylib which outputs a target specific shared object file.

Here’s an example release with all the architectures we support.

Step 3: Create the SDKs

Most languages have built-in FFI support. We ship libextism with a header file libextism.h

which acts as the IDL to the ABI. Lean heavily toward using the standard bindgen for your language

as they will automate the binding code for you. Bindings aren’t too hard to write,

but you can get bogged down in details and mistakes regarding memory management and ownership.

The code it generates is not always pleasant, but you can create an idiomatic native layer to

decouple from generated code.

Note: We started off putting all the libraries in the monorepo for building and testing simplicity, but eventually moved the SDKs out to their own repos.

Step 4: Install Script

Extism ships with a CLI for a few purposes. One core features we added is pullling down the latest release for your target machine. and putting it in a place where the SDKs can easily find it.

Iterating and Scaling

This initial setup let us build SDK support very quickly and easily. It made maintenance easier as it allowed us ship updates to the core Extism runtime as we improved it without changing any of the SDKs. It also made it easy for the community to pick up new languages and experiment. They just had to write or generate FFI bindings to the shared object, which you can mostly do with limited low-level knowledge.

Eventually, you’ll find yourself wanting a more integrated experience. You can start streamlining languages as they pick up adoption. For example, some package managers might allow you to invoke or replace the need to use the Extism CLI to get the shared object. Or maybe you can bundle the shared object inside the package, a “fat” package. Or maybe you decide to upgrade and write some typesafe bindings in rust, and now you’re relying on the rust library directly and statically compiling it in.

This is mostly how Extism grew. As languages picked up steam we focused on improving the DX for each in iterative steps. But we always have the fallback shared object process to bootstrap new platforms.

How I’d do it today

The Extism philosophy of “running everywhere” is fairly extreme. In practice, especially if you are shipping some kind of end product, it makes sense to focus your efforts on a few languages up front. These days I would recommend having a good strategy for your native language (rust in our case), python, and javascript. That’s going to cover the majority of your early users. It’s also going to force you to think about supporting multiple concurrency paradigms up front.

But still, I think releasing a shared object allows for easy experimentation and low maintenance overhead and is worth doing up front, especially if you have a developer focused project. If I were to start over today, I’d consider a system to manage this for you like UniFFI.

Note: I can’t recall exactly who originated this architecture, but I can’t take credit. It was either Zach or Steve.